Did Slave Owners Rape Little Slave Girls

Scars of Gordon, a whipped Louisiana slave, photographed in April 1863 and later on distributed by abolitionists.

Bill of sale for the auction of the "Negro Boy Jacob" for "Eighty Dollars and a one-half" (equivalent to $1,423 in 2020) to satisfy a money judgment against the "holding" of his owner, Prettyman Boyce. October 10, 1807. Click on photo for consummate transcription.

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were oftentimes separate by the auction of ane or more than members, commonly never to see or hear of each other again.[1]

The argue over slave handling [edit]

In the decades earlier the American Civil War, defenders of slavery oftentimes argued that slavery was a positive good, both for the enslavers and the enslaved people. They defended the legal enslavement of people for their labor every bit a chivalrous, paternalistic institution with social and economic benefits, an important bulwark of civilisation, and a divine establishment similar or superior to the complimentary labor in the Due north.[2] [three]

Some slavery advocates asserted that many slaves were content with their state of affairs. African-American abolitionist J. Sella Martin countered that apparent "contentment" was in fact a psychological defense to dehumanizing brutality of having to show to their spouses being sold at auction and daughters raped.[4] [5]

After Ceremonious State of war and emancipation, White Southerners adult the pseudohistorical Lost Crusade mythology in order to justify White supremacy and segregation. This mythology deeply influenced the mindset of White Southerners, influencing textbooks well into the 1970s.[a] One of its tenets was the myth of the true-blue slave. In reality, the enslaved people "badly sought freedom". While 180,000 African-American soldiers fought in the Usa Ground forces during the Civil War, no slave fought as a soldier for the Confederacy.[7]

Legal regulations [edit]

Legal regulations of slavery were chosen slave codes. In the territories and states established subsequently the United states of america became independent, these slave codes were designed by the politically dominant planter course in lodge to make "the region rubber for slavery".[viii]

In North Carolina, slaves were entitled to be clothed and fed, and murder of a slave was punishable. But slaves could non requite testimony against whites nor could they initiate legal actions. There was no protection confronting rape. "The entire system worked against protection of slave women from sexual assault and violence".[9]

Living atmospheric condition [edit]

Compiling a multifariousness of historical sources, historian Kenneth Chiliad. Stampp identified in his archetype work The Peculiar Institution reoccurring themes in slavemasters' efforts to produce the "platonic slave":

- Maintain strict field of study and unconditional submission.

- Create a sense of personal inferiority, and so that slaves "know their identify."

- Instill fearfulness.

- Teach servants to take involvement in their master's enterprise.

- Prevent access to education and recreation, to ensure that slaves remain uneducated, helpless, and dependent.[10] [11]

Punishment and abuse [edit]

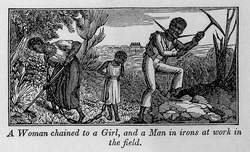

Abolitionist cartoon showing enslaved people beingness tortured

Slaves were punished by whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, mutilation, branding, rape, and imprisonment. Punishment was oft meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but sometimes abuse was performed to re-affirm the dominance of the master (or overseer) over the slave.[12]

Pregnancy was not a barrier to punishment; methods were devised to administer lashings without harming the infant. Slave masters would dig a hole large enough for the woman's stomach to prevarication in and proceed with the lashings.[13]

Slave overseers were authorized to whip and punish slaves. One overseer told a company, "Some Negroes are determined never to let a white man whip them and will resist yous, when yous attempt information technology; of grade you must kill them in that case."[14] A former slave describes witnessing females being whipped: "They usually screamed and prayed, though a few never fabricated a sound."[15]

In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass describes the cowskin whip:

The cowskin ... is made entirely of untanned, but stale, ox hide, and is nearly every bit hard as a piece of well-seasoned live oak. Information technology is made of diverse sizes, but the usual length is about iii feet. The office held in the hand is nearly an inch in thickness; and, from the extreme end of the butt or handle, the cowskin tapers its whole length to a bespeak. This makes it quite elastic and springy. A blow with it, on the hardest dorsum, will gash the flesh, and make the blood start. Cowskins are painted red, blue and green, and are the favorite slave whip. I call back this whip worse than the "cat-o'nine-tails." It condenses the whole strength of the arm to a unmarried point, and comes with a spring that makes the air whistle. It is a terrible instrument, and is then handy, that the overseer can always have it on his person, and fix for use. The temptation to use it is ever strong; and an overseer tin can, if tending, always accept cause for using it.[16]

The results of harsh punishments are sometimes mentioned in paper ads describing runaway slaves. One ad describes a woman of about 18 years, named Patty: "Her dorsum appears to accept been used to the whip."[17]

A metallic collar could be put on a slave. Such collars were thick and heavy; they often had protruding spikes which impeded piece of work as well as residuum. Louis Cain, a survivor of slavery, described the penalisation of a fellow slave: "One nigger run to the woods to be a jungle nigger, simply massa cotched him with the dog and took a hot iron and brands him. Then he put a bell on him, in a wooden frame what skid over the shoulders and under the arms. He made that nigger wear the bell a year and took it off on Christmas for a present to him. It sho' did make a good nigger out of him."[xviii]

The branding of slaves for identification was mutual during the colonial era; however, by the nineteenth century it was used primarily every bit punishment. Mutilation of slaves, such as castration of males, removing a front tooth or teeth, and amputation of ears was a relatively mutual punishment during the colonial era, still used in 1830: it facilitated their identification if they ran away. Whatsoever penalty was permitted for delinquent slaves, and many bore wounds from shotgun blasts or canis familiaris bites inflicted by their captors.[nineteen]

Slaves were punished for a number of reasons: working too slowly, breaking a law (for example, running away), leaving the plantation without permission, insubordination, impudence as divers by the owner or overseer, or for no reason, to underscore a threat or to assert the owner'due south dominance and masculinity. Myers and Massy depict the practices: "The penalization of deviant slaves was decentralized, based on plantations, and crafted so equally non to impede their value as laborers."[20] Whites punished slaves publicly to set an example. A human being named Harding describes an incident in which a adult female assisted several men in a minor rebellion: "The women he hoisted upwards past the thumbs, whipp'd and slashed her [sic] with knives before the other slaves till she died."[21] Men and women were sometimes punished differently; according to the 1789 study of the Virginia Commission of the Privy Council, males were oftentimes shackled but women and girls were left complimentary.[21]

Wilma Dunaway notes that slaves were ofttimes punished for their failure to demonstrate due deference and submission to whites. Demonstrating politeness and humility showed the slave was submitting to the established racial and social order, while failure to follow them demonstrated insolence and a threat to the social bureaucracy. Dunway observes that slaves were punished almost equally often for symbolic violations of the social club every bit they were for physical failures; in Appalachia, two-thirds of whippings were done for social offences versus i-third for physical offences such equally depression productivity or property losses.[22]

Education and access to information [edit]

Slave owners greatly feared slave rebellions.[23] About of them sought to minimize slaves' exposure to the outside world to reduce the adventure. The desired outcome was to eliminate slaves' dreams and aspirations, restrict access to information about escaped slaves and rebellions, and stifle their mental faculties.[24]

Pedagogy slaves to read was discouraged or (depending upon the state) prohibited, and then every bit to hinder aspirations for escape or rebellion. Slaveowners believed slaves with cognition would become morose, if non insolent and "uppity". They might acquire of the Secret Railroad: that escape was possible, that many would help, and that there were sizeable communities of formerly enslaved Blacks in Northern cities.[25] In response to slave rebellions such as the Haitian Revolution, the 1811 German Coast Uprising, a failed uprising in 1822 organized by Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, some states prohibited slaves from holding religious gatherings, or whatever other kind of gathering, without a white person present, for fear that such meetings could facilitate communication and lead to rebellion and escapes.

In 1841, Virginia punished violations of this law by 20 lashes to the slave and a $100 fine to the teacher, and North Carolina by 39 lashes to the slave and a $250 fine to the teacher.[25] In Kentucky, education of slaves was legal but virtually nonexistent.[25] Some Missouri slaveholders educated their slaves or permitted them to exercise and so themselves.[26]

Medical treatment [edit]

The quality of medical care to slaves is uncertain; some historians conclude that considering slaveholders wished to preserve the value of their slaves, they received the same care as whites did. Others conclude that medical intendance was poor. A bulk of plantation owners and doctors balanced a plantation need to coerce as much labor as possible from a slave without causing death, infertility, or a reduction in productivity; the effort by planters and doctors to provide sufficient living resources that enabled their slaves to remain productive and bear many children; the impact of diseases and injury on the social stability of slave communities; the extent to which illness and mortality of sub-populations in slave society reflected their unlike environmental exposures and living circumstances rather than their alleged racial characteristics.[27] [ folio needed ] [28] Slaves may take also provided adequate medical care to each other.[29] [28]

According to Michael Due west. Byrd, a dual system of medical intendance provided poorer care for slaves throughout the South, and slaves were excluded from proper, formal medical preparation.[30] This meant that slaves were mainly responsible for their own care, a "health subsystem" that persisted long after slavery was abolished.[31]

Medical care was usually provided by fellow slaves or past slaveholders and their families, and merely rarely past physicians.[32] [33] Intendance for sick household members was more often than not provided by women. Some slaves possessed medical skills, such as cognition of herbal remedies and midwifery and oftentimes treated both slaves and non-slaves.[32] Covey suggests that because slaveholders offered poor treatment, slaves relied on African remedies and adapted them to Northward American plants.[34] Other examples of improvised wellness care methods included folk healers, grandmother midwives, and social networks such every bit churches, and, for meaning slaves, female person networks. Slave-owners would sometimes too seek healing from such methods in times of ill health.[35]

Researchers performed medical experiments on slaves, who could non refuse, if their owners permitted information technology. They ofttimes displayed slaves to illustrate medical atmospheric condition.[36] Southern medical schools advertised the ready supply of corpses of the enslaved, for dissection in anatomy classes, as an incentive to enroll.[37] : 183–184

Separation of families [edit]

Plantation slave cabins, South Carolina Depression State

In the introduction to the oral history project, Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation, the editors wrote:

Every bit masters applied their stamp to the domestic life of the slave quarter, slaves struggled to maintain the integrity of their families. Slaveholders had no legal obligation to respect the sanctity of the slave'due south spousal relationship bed, and slave women— married or single – had no formal protection against their owners' sexual advances. ...Without legal protection and subject to the chief's whim, the slave family was ever at risk.[38]

Elizabeth Keckley, who grew up enslaved in Virginia and later became Mary Todd Lincoln's personal modiste, gave an account of how she had witnessed Little Joe, the son of the cook, being sold to pay his enslaver's bad debt:

Joe's mother was ordered to wearing apparel him in his best Sunday clothes and send him to the house, where he was sold, like the hogs, at then much per pound. When her son started for Petersburgh, ... she pleaded piteously that her male child not be taken from her; simply master quieted her by telling that he was going to town with the wagon, and would be back in the morning. Morning came, just piffling Joe did not return to his female parent. Morning after morning time passed, and the mother went down to the grave without ever seeing her kid again. One day she was whipped for grieving for her lost boy.... Burwell never liked to see his slaves vesture a sorrowful face, and those who offended in this way were always punished. Alas! the sunny face of the slave is not always an indication of sunshine in the heart.[39]

Between 1790 and 1860, about 1 million enslaved people were forcefully moved from the states on the Atlantic seabord to the interior in a 2nd Middle Passage.[40] This normally involved the separation of children from their parents and of husbands from their wives.[41]

Rape and sexual abuse [edit]

Owners of enslaved people could legally use them every bit sexual objects. Therefore, slavery in the U.s.a. encompassed wide-ranging rape and sexual abuse, including many forced pregnancies, in guild to produce children for sale.[42] Many slaves fought back against sexual attacks, and some died resisting them; others were left with psychological and concrete scars.[43] Historian Nell Irvin Painter describes the effects of this abuse as "soul murder".[44]

Rape laws in the Due south embodied a race-based double standard. Black men defendant of rape during the colonial period were oftentimes punished with castration, and the penalty was increased to death during the Antebellum Period;[45] however, white men could legally rape their female slaves.[45] Men and boys were likewise sexually abused by slaveholders.[46] Thomas Foster says that although historians take begun to cover sexual abuse during slavery, few focus on sexual abuse of men and boys considering of the supposition that but enslaved women were victimized. Foster suggests that men and boys may have besides been forced into unwanted sexual action; one problem in documenting such corruption is that they, of course, did non bear mixed-race children.[47] : 448–449 Both masters and mistresses were thought to have abused male slaves.[47] : 459

The mistreatment of slaves often included rape and the sexual corruption of women. The sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in historical Southern culture and its view of the enslaved every bit property.[42] Although Southern mores regarded white women equally dependent and submissive, black women were ofttimes consigned to a life of sexual exploitation.[42] Racial purity was the driving force behind the Southern civilization'south prohibition of sexual relations between white women and blackness men; notwithstanding, the same civilization protected sexual relations between white men and black women. The result was a number of mixed-race offspring.[42] Many women were raped, and had piddling control over their families. Children, gratuitous women, indentured servants, and men were not allowed from abuse by masters and owners. Children, specially young girls, were often subjected to sexual abuse by their masters, their masters' children, and relatives.[48] Similarly, indentured servants and slave women were frequently abused. Since these women had no command over where they went or what they did, their masters could dispense them into situations of high risk, i.eastward. forcing them into a dark field or making them sleep in their main's chamber to be available for service.[49] Costless or white women could charge their perpetrators with rape, just slave women had no legal recourse; their bodies legally belonged to their owners.[50]

After 1662, when Virginia adopted the legal doctrine partus sequitur ventrem, sexual relations betwixt white men and black women were regulated by classifying children of slave mothers as slaves regardless of their male parent'southward race or status. Particularly in the Upper Due south, a population developed of mixed-race offspring of such unions (meet children of the plantation), although white Southern guild claimed to abhor miscegenation and punished sexual relations between white women and black men every bit damaging to racial purity.

Slave breeding [edit]

Slave breeding was the attempt by a slave-possessor to influence the reproduction of his slaves for profit.[51] It included forced sexual relations between male and female person slaves, encouraging slave pregnancies, sexual relations between principal and slave to produce slave children and favoring female slaves who had many children.[51]

For example, Frederick Douglass (who grew up every bit a slave in Maryland) reported the systematic separation of slave families and widespread rape of slave women to boost slave numbers.[52] With the development of cotton wool plantations in the Deep South, planters in the Upper Southward often bankrupt upwardly families to sell "surplus" male slaves to other markets. In addition, court cases such every bit those of Margaret Garner in Ohio or Celia, a slave in 19th-century Missouri, dealt[ how? ] with women slaves who had been sexually abused by their masters.[53]

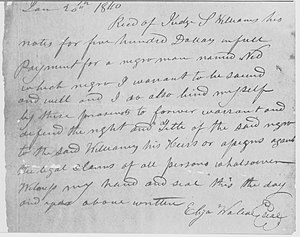

Receipt for $500 payment ($10,300, adjusted for inflation equally of 2007[update]) for slave, 1840: "Recd of Judge Southward. Williams his notes for five hundred Dollars in total payment for a negro human named Ned which negro I warrant to be sound and well and I practice demark myself by these presents to forever warrant and defend the correct and Title of the said negro to the said Williams his heirs or assigns against the legal claims of all persons whatsoever. Witness my hand and seal this day and year above written. Eliza Wallace [seal]"

Concubines and sexual slaves [edit]

The evidence of white men raping slave women was obvious in the many mixed-race children who were born into slavery and part of many households. In some areas, such mixed-race families became the core of domestic and household servants, as at Thomas Jefferson'southward Monticello. Both his begetter-in-law and he took mixed-race enslaved women as concubines later being widowed; each man had vi children by those enslaved women. Jefferson's young concubine, Sally Hemings, was 3/4 white, the girl of his male parent-in-law John Wayles, making her the half-sis of his late married woman.

Many female slaves (known as "fancy maids") were sold at sale into concubinage or prostitution, which was called the "fancy merchandise".[45] Concubine slaves were the simply female slaves who allowable a college price than skilled male person slaves.[54]

Mixed-race children [edit]

By the turn of the 19th century many mixed-race families in Virginia dated to Colonial times; white women (more often than not indentured servants) had unions with slave and free African-descended men. Considering of the mother's status, those children were born complimentary and frequently married other free people of color.[55]

Given the generations of interaction, an increasing number of slaves in the U.s.a. during the 19th century were of mixed race. With each generation, the number of mixed-race slaves increased. The 1850, demography identified 245,000 slaves equally mixed-race (called "mulatto" at the time); past 1860, in that location were 411,000 slaves classified as mixed-race out of a total slave population of 3,900,000.[43]

Notable examples of mostly-white children built-in into slavery were the children of Sally Hemings, who information technology has been speculated are the children of Thomas Jefferson. Since 2000 historians take widely accepted Jefferson'southward paternity, the change in scholarship has been reflected in exhibits at Monticello and in recent books virtually Jefferson and his era. Some historians, notwithstanding, continue to disagree with this conclusion.

Speculation exists on the reasons George Washington freed his slaves in his volition. Ane theory posits that the slaves included ii half-sisters of his wife, Martha Custis. Those mixed-race slaves were born to slave women endemic by Martha's father, and were regarded inside the family as having been sired past him. Washington became the owner of Martha Custis'due south slaves nether Virginia police force when he married her and faced the ethical conundrum of owning his wife's sisters.[56]

Planters with mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their education (occasionally in northern schools) or apprenticeship in skilled trades and crafts. Others settled property on them, or otherwise passed on social capital past freeing the children and their mothers. While fewer in number than in the Upper South, costless blacks in the Deep Due south were often mixed-race children of wealthy planters and sometimes benefited from transfers of holding and social capital. Wilberforce Academy, founded past Methodist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) representatives in Ohio in 1856, for the teaching of African-American youth, was during its early history largely supported by wealthy southern planters who paid for the education of their mixed-race children. When the American Ceremonious War bankrupt out, the majority of the school's 200 students were of mixed race and from such wealthy Southern families.[57] The college closed for several years before the AME Church bought and operated it.

Summaries by survivors of slavery [edit]

Historian Ty Seidule uses a quote from Frederick Douglass's autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom to describe the experience of the average male slave every bit being "robbed of wife, of children, of his difficult earnings, of home, of friends, of social club, of knowledge, and of all that makes his life desirable."[58]

A quote from a letter by Isabella Gibbons, who had been enslaved by professors at the University of Virginia, is now engraved on the academy'due south Memorial to Enslaved Laborers:

Can nosotros forget the crevice of the whip, the cowhide, whipping-post, the sale-block, the spaniels, the atomic number 26 collar, the negro-trader violent the young child from its female parent's chest as a whelp from the lioness? Have we forgotten that by those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race accept been killed? No, we have not, nor ever volition.[59]

Meet also [edit]

- History

- Slavery in the colonial history of the The states

- Colonial American bastardy laws

- History of sexual slavery in the The states

- Female slavery in the United States

- Enslaved women's resistance in the United States and Caribbean

- Marriage and procreation

- Marriage of enslaved people (Us)

- Plaçage, interracial common police force marriages in French and Spanish America, including New Orleans

- Sexual slavery

- Partus sequitur ventrem

- Other

- Inability in American slavery

- Delphine LaLaurie

- 40 acres and a mule

- Freedmen'southward Agency

- Lumpkin'southward Jail

- A negro male child tortured

Notes and references [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ "The Lost Cause became a movement, an ideology, a myth, even a civil religion that would unite starting time the white South and eventually the nation around the meaning of the Ceremonious War. The Lost Crusade might have helped unite the land and bring the Southward dorsum into the nation far more than rapidly than bloody ceremonious wars in other lands. But this lie came at a horrible, deadly, incommunicable cost to the nation, a cost we are even so paying today. The Lost Crusade created a flawed memory of the Civil State of war, a lie that formed the ideological foundation for white supremacy and Jim Crow laws, which used vehement terror and de jure segregation to enforce racial control. I grew upwards on the evil lies of the Lost Cause."[6]

References [edit]

- ^ Rosenwald, Marking (December 20, 2019). "Terminal Seen Ads". Washington Post. Retropod. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved Dec 29, 2019.

- ^ Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 58, p. 480

- ^ Allan Kulikoff, Abraham Lincoln and Karl Marx in Dialogue, Oxford Academy Press, 2018, p. 55

- ^ Davis, Inhuman Bondage 228-229

- ^ Johnson, Smith, Africans 371

- ^ Seidule, Lee and Me 30

- ^ Seidule, Lee and Me 32

- ^ Berlin, Generations 165

- ^ Yellin (ed.), Incidents Editor'due south note ii on folio 287

- ^ Stampp, Kenneth (1956). The peculiar institution: slavery in the ante-bellum Southward . Vintage. pp. 141–148. Archived from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-09 .

- ^ A turbulent voyage : readings in African American studies. Hayes, Floyd Due west. (Floyd Windom) (3rd ed.). Lanham, Dr..: Rowman & Littlefield. 2000. p. 277. ISBN0939693526. OCLC 44998768.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Moore, Slavery 114

- ^ Greyness White, Deborah (2013). Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans. Bedford/ St. Martins. ISBN978-0-312-19729-2.

- ^ Howard Zinn A People's History of the U.s.a.. New York: Harper Collins Publications, 2003.

- ^ Work Projects Administration, ed. (2017). The Voices From The Past – Hundreds of Testimonies past Former Slaves In One Volume: The Story of Their Life – Interviews with People from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia... ISBN978-80-268-7377-8.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1855). My Bondage and My Liberty. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan. p. 103.

- ^ Virginia Herald and Fredericksburg Advertiser, June 5, 1788, quoted in Brown, DeNeen L. (May 1, 2017). "Hunting downwardly runaway slaves: The savage ads of Andrew Jackson and 'the master class'". Washington Mail.

- ^ Nair, P. Sukumar, ed. (2011). Man Rights In A Changing World. Gyan Publishing House. p. 111. The words of Cain too in: Rawick, George P. (1972). The American Slave: a Composite Autobiography: From sundown to sunup: the making of the Black community. p. 58.

- ^ Christian, Bennet, Black Saga 102-103

- ^ Myers, Martha, and James Massey. "Race, Labor, and Penalisation in Postbellum Georgia." 38.2 (1991): 267–286.

- ^ a b Lasgrayt, Deborah. Ar'n't I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation S, 2nd edition, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1999

- ^ Dunaway, Wilma A. (2003). Slavery in the American Mountain South. Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–171. ISBN978-0521012157.

- ^ Aptheker, Henry (1993). American Negro Slave Revolts (50th Anniversary ed.). New York: International Publishers. ISBN978-0717806058.

Widespread fear of slave rebellion was characteristic of the South (p. 39).

- ^ Christian, Bennet, Black Saga 90

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Slavery 616-617

- ^ Stone, Jeffery C., Slavery, Southern culture, and education in Footling Dixie, Missouri, 1820–1860, CRC Press, 2006, p 38

- ^ Kiple, King, Dimension

- ^ a b McBride, D. (2005). "Slavery As It Is:" Medicine and Slaves of the Plantation S. OAH Magazine Of History, 19(5), 37.

- ^ Covey, Slave Medicine 5-6

- ^ Covey, Slave Medicine 4-v, citing Byrd, p 200

- ^ Covey, Slave Medicine 4, citing Byrd, p 200

- ^ a b Burke, Diane Mutti (2010). On Slavery'due south Border: Missouri's Small Slaveholding Households, 1815–1865. Academy of Georgia Printing. p. 155.

- ^ Covey, Slave Medicine five

- ^ Covey, Slave Medicine 5

- ^ McBride, D. (2005). "Slavery As It Is:" Medicine and Slaves of the Plantation South. OAH Magazine Of History, xix(5), 38.

- ^ Covey, Slave Medicine 30

- ^ von Daacke, Kirt (2019). "Anatomical Theater". In McInnis, Maurie D.; Nelson, Louis P. (eds.). Educated in Tyranny: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson'south University. Academy of Virginia Press. pp. 171–198, at pp. 183–184. ISBN978-0813942865.

- ^ Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation edited by Ira Berlin, Marc Favreau, and Steven F. Miller, pp. 122–three. ISBN 978-1-59558-228-seven

- ^ Keckley, 1868, p. 12 Backside the Scenes or, Thirty years a slave, and Iv Years in the White House Archived 2018-12-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berlin, Generations 15, 161

- ^ Berlin, Generations 169

- ^ a b c d Moon, Dannell (2004). "Slavery". In Smith, Merril D. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Rape. Greenwood. p. 234.

- ^ a b Marable, p 74

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin (1995). Soul Murder and Slavery. Markham Printing Fund. p. 7. ISBN9780918954626.

child abuse, sexual corruption, sexual harassment, rape, battering. Psychologists aggregate the effects of these all-as well-familiar practices in the phrase "soul murder"

- ^ a b c Moon, p 235

- ^ Getman, Karen A. "Sexual Control in the Slaveholding South: The Implementation and Maintenance of a Racial Caste Organisation," Harvard Women'southward and Police Journal, 7, (1984), 132.

- ^ a b Foster, Thomas (2011). "The Sexual Abuse of Black Men nether American Slavery". Journal of the History of Sexuality. xx (3): 445–464. doi:10.1353/sex.2011.0059. PMID 22175097. S2CID 20319327.

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin, "Soul Murder and Slavery: Toward A Fully Loaded Cost Bookkeeping," U.S. History equally Women'southward History, 1995, p 127.

- ^ Block, Sharon. "Lines of Color, Sexual practice, and Service: Sexual Coercion in the Early Republic," Women's America, p 129-131.

- ^ Block, Sharon. "Lines of Colour", 137.

- ^ a b Marable, Manning, How capitalism underdeveloped Blackness America: problems in race, political economy, and society South Terminate Press, 2000, p 72

- ^ Douglass, Frederick Autobiography of Frederick Douglass Archived 2011-08-29 at the Wayback Motorcar, Autobiography of Frederick Douglass, 1845. Book. Retrieved June 10, 2008

- ^ Melton A. McLaurin, Celia, A Slave, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1991, pp. 10–fourteen

- ^ Baptist, Edward E. "'Cuffy', 'Fancy Maids', and 'One-Eyed Men': Rape Commodification, and the Domestic Slave Trade in the United States", in The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas, Walter Johnson (Ed.), Yale University Printing, 2004

- ^ Paul Heinegg, Complimentary African Americans in Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina Archived 2012-09-nineteen at the Wayback Machine, 1998–2005

- ^ Wiencek, Henry (Nov 15, 2003). An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN978-0374175269.

- ^ James T. Campbell, Songs of Zion, New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 1995, p.259-260, accessed 13 Jan 2009

- ^ Seidule, Lee and Me 244

- ^ "Memorial to Enslaved Laborers: History". Academy of Virginia . Retrieved December xv, 2021.

Bibliography [edit]

Secondary sources [edit]

- Bankole, Katherine Kemi, Slavery and Medicine: Enslavement and Medical Practices in Antebellum Louisiana, Garland, 1998

- Ball, Edward, Slaves in the Family, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998

- Berlin, Ira (2003). Generations of Captivity. ISBN0-674-01061-2.

- Byrd, W. Michael, and Clayton, Linda A., An American Health Dilemma: Vol i: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race: Ancestry to 1900. Psychology Press, 2000.

- Campbell, James T. Songs of Zion, New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1995

- Christian, Charles M.; Bennet, Sari (1998). Black Saga: The African American Experience : A Chronology. Basic Civitas Books.

- Covey, Herbert C. (2008). African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments. Lexington Books.

- Davis, David Brion (2006). Inhuman Bondage: The Ascension and Fall of Slavery in the New World. New York: Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0195339444.

- Heinegg, Paul, Complimentary African Americans in Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina, 1998–2005

- Jacobs, Harriet A. (2000). Yellin, Jean Fagan (ed.). Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself. Enlarged Edition. Edited and with an Introduction by Jean Fagan Yellin. Now with "A True Tale of Slavery" by John S. Jacobs. Cambridge: Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-6740-0271-5.

- Johnson, Charles; Smith, Patricia (1999). Africans in America: America's Journey Through Slavery. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; King, Virginia Himmeisteib (30 Oct 2003). Another Dimension to the Black Diaspora: Nutrition, Affliction, and Racism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0521528504.

- Marable, Manning, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Blackness America: Bug in Race, Political Economy, and Social club S Stop Printing, 2000

- Moon, Dannell, "Slavery", in Encyclopedia of Rape, Merril D. Smith (Ed.), Greenwood Publishing Grouping, 2004

- Moore, Wilbert Ellis (1980). American Negro Slavery and Abolition: A Sociological Report. Ayer Publishing.

- Morgan, Philip D. "Interracial Sex In the Chesapeake and the British Atlantic Globe c. 1700–1820". In Jan Lewis, Peter S. Onuf. Sally Hemings & Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Civilization, University of Virginia Press, 1999

- Rothman, Joshua D. Notorious in the Neighborhood: Sex and Interracial Relationships Across the Color Line in Virginia, 1787–1861, University of North Carolina Printing, 2003

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Seidule, Ty (2020). Robert East. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause. New York: St. Martin'southward Press. ISBN9781250239266.

- Silkenat, David. Scars on the Land: An Environmental History of Slavery in the American South. New York: Oxford University Printing, 2022.

Primary sources [edit]

- Dresser, Amos (1836). "Slavery in Florida. Letters dated May 11 and June 6, 1835, from the Ohio Atlas". The narrative of Amos Dresser: with Rock'southward letters from Natchez, an obituary find of the author, and two letters from Tallahassee, relating to the treatment of slaves.

- Rankin, John. Letters on Slavery.

- Eastward. Thomas (1834). A concise view of the slavery of the people of color in the United States; exhibiting some of the most affecting cases of cruel and fell treatment of the slaves by their almost inhuman and brutal masters; not heretofore published: and likewise showing the accented necessity for the most speedy abolition of slavery, with an endeavour to bespeak out the all-time means of effecting information technology. To which is added, A short address to the gratis people of color. With a selection of hymns, &c. &c.

- New-England Anti-Slavery Society (1834). Proceedings of the New-England Anti-Slavery Convention, held in Boston on the 27th, 28th and 29th of May, 1834. Boston. Archived from the original on 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2019-11-12 .

- New-England Anti-Slavery Society (1835). Second annual study of the board of managers of the New-England Anti-Slavery Society: presented January. 15, 1834: with an appendix. pp. four–five. Archived from the original on 2020-06-26. Retrieved 2019-11-12 .

- Weld, Theodore Dwight; American Anti-Slavery Society (1839). American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Yard Witnesses. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society. p. three.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treatment_of_slaves_in_the_United_States

0 Response to "Did Slave Owners Rape Little Slave Girls"

Post a Comment